THEORIES ABOUT THE CAUSES OF DEPRESSION Guilt Depression-prone people are super aware of their wrong doings--and feel especially guilty. Mowrer, et al (1975) does not believe this guilt necessarily involves some highly immoral behavior, such as intense hostility or vile impulses, but rather could be the accumulation of many ordinary "sins." We all do inconsiderate things: selfish acts, hurtful comments, just not thinking of others, etc. Our society encourages us to look out for #1 first or "do your own thing." As Mowrer observes, since the Protestants protested confessing to a priest 500 years ago, the Protestant religions provide no authorized way to confess our sins and atone. And, because we hold inside "real guilt" for what we have done, we become depressed and may have other neurotic reactions. (Other theorists say it isn't guilt as much as being ashamed of not trying harder.) Mowrer's solution was to form "integrity groups" (modeled after the small early Christian congregations) in which understanding, permanent friends listened to our shortcomings (our "sins"), forgave us, and then helped us make up for the harm we have done. Regret for things we did can be tempered by time; it is regret for the things we did not do that is inconsolable.-Sydney J. Harris Guilt isn't always the result of doing something inconsiderate or immoral. Often it is just not doing what you think you should--"I should never have let my son go out with that crowd," "I should have known they weren't telling me the truth," "I should have kept better records for taxes." In this case, you may be assuming too much responsibility for whatever happened, setting impossible (perfectionistic) standards, and/or engaging in irrational thinking (see #6 and #7 above). Your mistaken views of the world and your unreasonable expectations of yourself may cause guilt. Guilt may cause depression. Or there is another possibility: whoever makes us feel guilty is resented. In the case of guilt or regrets, you make yourself feel badly; thus, you become angry at yourself, and that anger is assumed by analysts to be the cause of depression. Handling guilt and regrets is dealt with in the next section. Unmet dependency Some psychoanalysts and interpersonal therapists have looked into the history of depressives and found over-protective, indulging, overly involved or over-controlling, restrictive parents. The child grows up with an "oral character:" dependent, low frustration tolerance, and so desperate to have people like them that they are submissive, manipulative, demanding and so on. Before becoming depressed they are described by therapists as "love addicts in a perpetual state of greediness...sending out a despairing cry for love" (Chodoff, 1974). Their self-esteem depends on the approval of others. When their dependency needs are not met, they become depressed and cry, just as they did as infants. Moreover, it usually makes us mad when we feel weak and dependent. So, an over-dependent depressed person may resist help ("You can't make me be productive and happy") and become hostile ("I will pay you back for not loving me"). Thus, the loss of love is a triple threat to a dependent person prone to depression: (a) sadness and panic occur because our vital, life-long struggle for security has been lost, (b) low self-esteem and hopelessness occur because "I have lost everything" or "I do not deserve anything" and (c) anger and resentment occur because "they have deserted me, a helpless child" (Zaiden, 1982). So, it isn't surprising that research confirms, especially for very needy people, the old saying, "you can't live with them; you can't live without them." Relationships (marital problems and stress with children) are the most common stresses associated with depression in women. And, relationships (good, caring, intimate ones) are the best protection against depression (Brown & Harris, 1978; Klerman & Weissman, 1982). See sections below on loss of a relationship and loneliness. These interpersonal, psychodynamic, and psychoanalytic therapists would say that explaining depression as a result of negative thoughts or a lack of social skills is superficial and foolishly ignores the life-long, internal struggle for love for survival. Likewise, this theory sounds very similar to the currently popular feminists' description of social pressures put on traditional women to give up their individuality ("be nice," serve and accommodate others, put your needs last) in order to be "loved." Evidence is accumulating for this kind of theory (Barnett & Gotlib, 1988), including relying on others for one's self-esteem (see chapter 8). Impossible goals or no goals Overly demanding parents who are critical, perfectionistic, and harshly punitive tend to have anxious, withdrawn, and sometimes hostile children who have an "I'm not OK" attitude (like Sooty Sarah). Perhaps they adopted the parents' impossible goals. On the other hand, Coopersmith's (1967) work suggests that uninvolved parents, who do not discipline consistently and/or do not provide moral guidelines for living, tend to have children with low self-esteem (and higher risk of depression). Losing one's goal or values may lead to depression too. Hirsch and Keniston (1970) studied 31 drop outs from Yale during the late 1960's--during the time of the drug counter-culture, hippies, flower people, anti-war demonstrations, etc. They did not flunk out; they just weren't interested. Indeed, nothing interested them very much. They seemed mildly depressed. But there had been no losses, no big stresses. Yet, one experience was common: loss of respect for their fathers. They had once idolized their fathers, but now could not accept their fathers' values. Middle-class materialism, money, and the country club weren't for them. They felt lost, unsure of what they wanted, and a little bored with it all. Thousands dropped out of school and traditional society during the 1960's and early 70's. This condition has been called "existential neurosis." Existential therapy aims to restore the person's sense of freedom and responsibility for his/her choices now and in the future. To do this, life must have meaning and purpose. (Note: the dropping out stopped in 1973-74 when we had a recession causing people to start worrying about making a living. The drop outs would be 45 to 50 years old now and have 20-year-old children.) Shame: feeling ashamed of yourself has to be depressing. A critical problem with several previous theories is that the origin of the depression is not clear, i.e. where exactly does the helplessness, the negative views, the irrational ideas, the faulty thinking, the self-criticism, the low self-esteem, etc., come from? The shame theory can not be faulted in this way; it identifies the origin as early childhood experiences. Shame is feeling you are inadequate, inferior, lacking, not good enough, "ashamed of myself." In contrast with fear which involves external threats, shame is when we feel disappointed about something inside us, our basic nature. Shame is an inner torment: feeling cowardice, stupid, unloved, worthless, "a bad person." We hide in shame, i.e. we "hang," turn, or cover our heads, we lower our eyes, we isolate ourselves. (There is a related dimension--shyness or bashfulness--but here we are dealing with self-loathing or feeling ashamed of oneself.) The great concern with addictions in the last 15-20 years has resulted in a new body of literature about the dysfunctional family, toxic parents, the inner child, codependency, adult children of alcoholics, support groups, etc. There are 100's of relevant books: Kaufman (1989, 1992), Bradshaw (1988, 1989), and Beattie (1989). The origin of shame is usually assumed to be in our infancy or childhood. Shaming is used for control by parents, by friends, by society. Some of the most hurtful discipline consists of shaming comments: "shame on you," "you embarrass me," "you really disappoint me when...." We say insulting things to children that we would never say to an adult: "stupid," "clumsy," "selfish," "sissy," "fatty," "it's all your fault," "you're terrible," "you're hateful," "stuck up," etc. Many adults vividly remember the sting of these comments. Siblings and peers are cruel: mocking, laughing at, teasing, calling names, etc. Children are slapped and whipped, overpowered and humiliated, their "will" broken. All of this may make a child feel ashamed (depressed) of him/herself. Even in adolescence we feel watched and judged (mistrusted); we are "shamed into" giving up crying and touching; we are looked down upon if we aren't successful, attractive, independent, and popular. We feel ashamed if we are poor and dress poorly, if we are over or under weight, if we can't express ourselves well or use poor grammar, if our grades are low, if we have few friends, etc. Some shame and anxiety may serve useful purposes, but it can be devastating. There is some data to support the shame-based theories. Andrews (1995) found that "deep shame," not just dissatisfaction, in women about their bodies (usually breasts, buttocks, stomach or legs) was powerfully related to suffering severe depression. If a female is physically or sexually abused as a child or as an adult, it increases the likelihood of depression four or five times! Only childhood abuse caused shame about the body in women, however. See Lisak (1995) for an impactful discussion of the effects of childhood abuse on males. The memories of our past--our childhood and adolescence--form our identity or our basic sense of self. Because we have shame-based families and cultures, shame gets connected with many things, such as our basic drives, interpersonal needs, feelings, and life purposes. Examples: much shame is attached to sexual drives (witness the uneasiness we feel about masturbation, not to mention homosexuality) and to hunger drives (witness the feeding problems of infants, the fights over food with children, and the eating disorders of young people). We are deeply hurt and made ashamed of our needs for closeness and security whenever a basic bond is broken by rejection, abuse, neglect, divorce, or smothering overprotection and overcontrol. Sometimes shame is connected with our bodies, our lack of competence, our life goals (witness others' reaction to someone wanting to be a popular singer or a girl wanting to be a mechanic or a boy wanting to be a nurse). Also, emotion-shame connections ("Don't cry!" or "Don't feel that way!" or "Stop sniffling or I'll spank you") are made and we become ashamed of crying, anger, fear, self-centeredness, even joy sometimes. And, in extreme cases, you can become ashamed of everything you are--of your entire self--"I am worthless." Shame is a powerful force but we can understand and overcome some of its sources. There seem to be several natural defenses used against self-attacking shame: · Striking out at others. Attacking others by being critical, sarcastic, or abusive are ways to repair a wounded ego and to protect our vulnerable weak parts from exposure. Acting superior and having contempt for others are other ways to sooth a hurting self. · Striving for power and being perfect. The wish of a child would be to make up for our weaknesses by becoming powerful and being perfect. · Blaming others. What better way to deny our weaknesses than to blame others for our problems or for the world's problems? · Being an overly nice people-pleaser or rescuer or self-sacrificing martyr. If you feel unworthy, your hope might be to compensate for it by being "real good." Being super nice often means pretending or lying about our feelings and true opinions, presumably because we are ashamed of our real selves. · The self can withdraw so deeply or shut off the outside world so completely (denial) that shameful actions or events just don't upset our self, in this way the self can't be hurt. Obviously, a person feeling shame but using these defenses would inflict shame on others; that is, wounds of shame are passed from parent to child. This is done by parents in a variety of ways: (a) verbal, sexual and physical abuse, (b) physical and emotional abandonment (the child may even be expected to take care of the parent's emotional needs), (c) thinking of children as insignificant inferiors to be dominated and blamed or as persons to be controlled by threats of rage, disapproval, and withdrawal of love or as persons to be taken care of excessively, and not told the truth because they are needy, fragile, and "can't understand" or as persons to stay emotionally enmeshed with because they are perfect, wonderful, can meet your needs, and may be the only ones that care for us. So, shame begets shame. What are the consequences of a shame-oriented family? Self-blame and criticism (like Sooty Sarah). Constantly comparing yourself with others and coming up short. Depression--we may dislike and disown parts of our self and even feel disdain for our self as a whole. The shamed person may engage in compulsive disorders--physical and sexual abuse, drug and alcohol addiction, anorexia-bulimia and obesity, workaholism, sex addictions, addictions to certain feelings (rage, being shamed and rejected), intellectualization, anti-social acting out, and other personality problems, including multiple personality. The list is long. Some of these "sick" behaviors, like addictions, help us hide our shame; some, like workaholism, try to make up for our weaknesses; some, like abuse, adopt the harmful behavior that was imposed on us; some, like criminal acts, reflect fear and hatred of the shaming techniques used against us. Shame operates inside all of us...it is a voice inside our head. The voice usually sounds like our parent. Sometimes the voice of shame is healthy and helpful; sometimes it is unhealthy and self-defeating. Nathanson (1995) should help you understand this complex emotion. Shame-based families often have unspoken but well understood "rules," such as: Don't have feelings or, at least, don't talk about them. Don't try to make things better--leave the family problems alone. Don't be who you really are; don't be frank and explicit; always manipulate others and pretend to be something different, such as something good, unselfish, and in control. Always take care of others, don't be selfish and upset others, and don't have fun. Don't get close to people, they won't like you if they know the truth. Rules such as this keep you weak, hopeless, immature, hurting, and unhealthy--depressed and maybe addicted as well. Discouragement is simply the despair of wounded self-love.-Francois De Fenelon Treatment, according to this theory, involves uncovering the sources of shame and recognizing the oppressing controls placed on you by internal voices of shame, family rules, and cultural-gender restrictions. Getting free may mean taking care of the hurt, scared little boy/girl inside, and building your self-esteem (see the later section on shame in this chapter and method #1 in chapter 14). Lacking self-control causes depression This explains why single women with little education and low income are the most likely to be depressed; they lack support and control over their lives. Also, dominated women report feeling they have "lost themselves." They are in a relationship in which they have lost the option of expressing their feelings openly, lost faith in their own ideas, lost reliance on their abilities and skills, lost their self-respect, and even lost their right to express anguish and despair (Jack, 1991). One can see why they must suppress their very being to keep their last shred of "love." Somehow these suppressed parts of our inner self must regain some control and learn to express themselves again. Rehm (1977) said the lack of self-help skills, i.e. not knowing how to get better, caused depressed people to over-emphasize the negative, set too high standards, and give too little self-reinforcement. Pyszczynski & Greenberg (1987) contended that depression is the inability to avoid focusing on one's self. D'Zurilla & Nezu (1982) claimed that poor interpersonal problem-solving skills cause depression; the skills depressed people often lack are (a) the ability to see alternative solutions, (b) the ability to develop detailed plans for reaching a final goal, and (c) the ability to make decisions. A sense of self-control is basic to these three skills. This way of viewing depression expands beyond the helplessness theory, which focuses on a pessimistic attitude; it emphasizes the importance of skills and cognitive techniques, which increase our ways and means of self-control as well as our optimism. This "explanation" of depression says much more than "take responsibility and heal thyself." To all of us, whether we are now depressed or not, it says that more research must be done. Miserable people can't learn what they need to know if wise people and science haven't uncovered the knowledge yet. It is a scientific necessity to laboriously test the effectiveness of each promising anti-depressive self-help method. There is already considerable evidence that some self-control methods work, but there are thousands of ordinary, everyday methods still to be tested with many different kinds of depressed people (maybe 100 years of research--let's get going!). Consider these complexities which need to be clarified: married people have more support, thus, less depression. Okay, but if women have more support than men, why are they more depressed? (See discussion of gender differences above and in chapter 9.) Moreover, we ordinarily think support is gotten by talking to someone, but Ross & Mirowsky (1989) reported that talking increased depression. How could this be? Perhaps talking (without problem-solving) drives others away and/or involves self-handicapping more than garnering support. For instance, research has shown that depressed people more than nondepressed people will actually fail a task (then talk about how awful they feel) in order to avoid doing more of a simple task (Weary and Williams, 1990). Like the motivated underachiever in chapter 4, some depressed people seem motivated to do poorly, have little self-control, and be depressed; depression may sometimes provide convenient excuses to ourselves and to others. This last explanation of depression emphasizes how uninformed the depressed person is about self-control and how much more science needs to learn about what helps and what harms depression. Summary of the Causes of Depression and How to Use Them These 14 theories give you ideas about how depression develops. Each theorist tends to assume that his/her explanation is the major cause. But, as you know, I don't think life is simple. I suspect that any one person's depression may have many causes. For instance, you might have a genetic propensity for depression. Then, you grew up in a shaming family who had a critical, pessimistic attitude. Feeling rejected anyway, you sensed and resented the hostility within the family, which lead to your gaining a lot of weight at puberty. All these factors together resulted in your having serious social problems and low self-esteem; you not only disliked yourself, you felt your family had caused a lot of your emotional problems--and told them so. The family had never been emotionally supportive anyway and honestly thought "if you are fat, stop eating" and "if you are unhappy, get happy--and drop all this psychology crap about parents being responsible." Being unable to deal with these personal problems, when your lover of two years, who you depended on greatly, decided to dump you, the depression was more than you could handle. You become lonely and sad all day, nothing seems fun any more, you gain more weight, feel tired and listless, become more self-critical and guilt-ridden, are unable to see anything good in your life now or in the future, and even have some thoughts of ending it all if your lover doesn't come back. The history is complex. You have serious depression and need professional help; it is too late to depend on will power alone. Yet, you must also learn about and help yourself. That's real life. You need to understand and consider how true each theory is of you--perhaps you need to read more or talk it through with a relative, friend, or counselor. Clearly, understanding the possible causes (in your case) helps you work out a possible solution. Consider the five parts or levels of any problem--behavior, emotions, skills, cognition, and unconscious factors--and then plan your attack, based on the rest of this chapter and chapters 11-15. Keep trying to climb out of the darkness until you feel better. Even if the depression is mild to moderate, get help if your self-help efforts don't work within a month or two. There are medications that relieve many people's depression; don't be foolish and reject drugs if psychological approaches don't work. Keep your hopes up. (source)

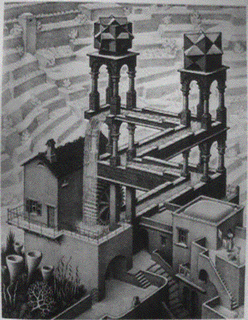

We have all admired the lithograph Waterfall by Maurits C. Escher (1961). His waterfall recycles its water after driving the water wheel. If it could work, this would be the ultimate perpetual motion machine that also delivers power! If we look closely, we see that Mr. Escher has deceived us, and any attempt to build this structure using solid masonry bricks would fail.

We have all admired the lithograph Waterfall by Maurits C. Escher (1961). His waterfall recycles its water after driving the water wheel. If it could work, this would be the ultimate perpetual motion machine that also delivers power! If we look closely, we see that Mr. Escher has deceived us, and any attempt to build this structure using solid masonry bricks would fail.